SISN Members Cross-examine SISN’s New Integrated IS Framework

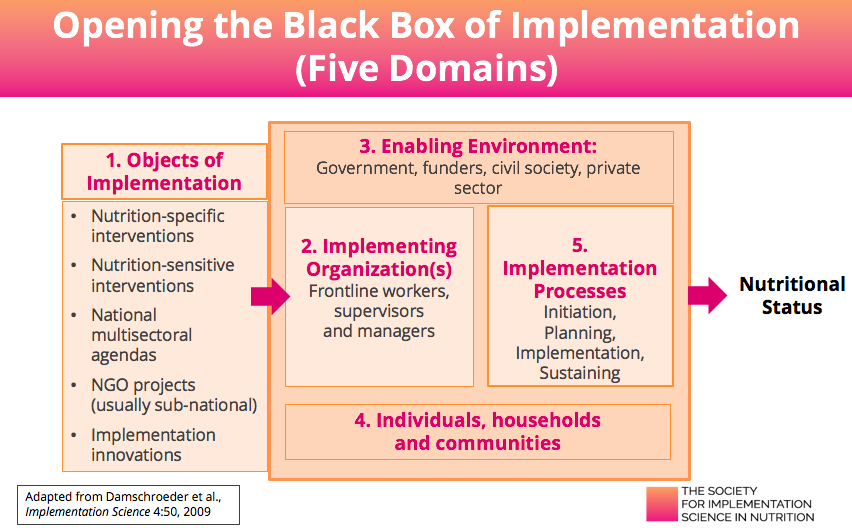

In June, David Pelletier presented SISN’s Integrated IS Framework in a webinar with a live Q&A. The feedback highlighted a number of questions for the Society to ponder in terms of the key issues faced by its members and how the framework can be interpreted for differing environments. It also highlighted some areas for developing the framework further. Most of the questions relate to the ‘Five Domains’ (slides 17 and 19), we’ve recapped those of particular interest below:

Q: Why a specific category for NGO projects? These can be nutrition-sensitive or specific and their level may vary (national, sub-national or community level)?

A: Although NGOs are implementing nutrition specific, nutrition sensitive interventions or innovative practices, typically they are doing so in ways that differ significantly from purely government programs. For example, they often have different time horizons (imposed by the donors); different sources of accountability (typically to the donors); tend to be sub-national, rather than national in scope; have access to greater resources and technical capacity; and may be closely linked to government structures and requirements (which can enable or inhibit large-scale implementation). In other words, the enabling environments, implementing organizations and implementing processes (Domains 2,3,5) all differ in the case of NGO projects and, as such, they present a very different set of opportunities and challenges for implementation (as well as implementation research).

Q: Please could you comment on how implementation science could be applied for Nutrition in Emergency.

A: This is an excellent point. We have not specifically identified the emergency sector as an “object of implementation”, but (as with NGO projects mentioned above) it differs in such important ways that this is something we should amend in future versions of the framework. Our conceptual framework is robust enough to be adapted to emergency settings, but as with all objects of implementation emphasis should be placed initially on locating, curating and promoting the use of existing frameworks, tools and guides, of which there are many.

Q: In the framework (slide 10), under enabling environments, I don’t see politics (either large P or small P, politics). Is there room in IS to look at the political as well as the technical?

A: Absolutely, yes politics/Politics are a hugely important factor that can either enable or inhibit implementation and these are taken into consideration as part of the ‘enabling environment’ as ‘characteristics’, ‘capacities’ and ‘dynamics’ that operate among, and within the Five Domains. Specifically, ‘dynamics’ would cover the bureaucratic and high level Politics that we all encounter and that can profoundly influence the quality and impact of implementation at country level.

A: Absolutely, yes politics/Politics are a hugely important factor that can either enable or inhibit implementation and these are taken into consideration as part of the ‘enabling environment’ as ‘characteristics’, ‘capacities’ and ‘dynamics’ that operate among, and within the Five Domains. Specifically, ‘dynamics’ would cover the bureaucratic and high level Politics that we all encounter and that can profoundly influence the quality and impact of implementation at country level.

Q: Context plays a big role in this framework. How well instrumented are we to make the distinctions that indicate to generality versus specificity of emerging knowledge?

A: Yes, context is key. It is vitally important to have a good understanding of the contextual framework in which you are operating to determine what needs to be addressed when planning and implementing in your own setting. So, if for example, evidence-based nutrition specific interventions or particular implementation practices and innovations are successful in one context, how do we determine the degree to which they might be successful in another?

My own view is that findings from one setting should be taken with a grain of salt and be subjected to very systematic analysis of whether, and how, it can fit into any new setting. To do so it is vital to have a deep understanding of the contextual factors in the new setting. This question nicely illustrates the whole concept of implementation science, in that any implementation must be preceded by a rigorous process of exploring, scoping and analysis to determine whether to ‘adopt’ or ‘adapt’ components from another setting. The default position would be to assume that most elements would need considerable adaptation across contexts, but as different elements are attempted in many different settings it may be that some emerge as potential areas for greater generalization and others are not.

It is important to bear in mind that, while contextual variations can (and do) limit the generalizability of findings and experiences across settings, what is fully generalizable is the PROCESS of systematically assessing, building on strengths and addressing weaknesses in the context. In other words, the IR process itself is fully generalizable.

Q: Regarding assessing readiness: Initiating scoping and engaging – how do we assess whether we have enough readiness from opinion leaders and decision makers at the outset of IR, and continued readiness as we proceed with IR?

A: This is a great question. I wish we would do this more systematically. I have never seen tools in the nutrition space for assessing readiness, but domestically in the US this is a hot topic and some very sophisticated tools have been developed. The references for some key ones are provided at the end of this blog.

Q: How do we educate donors on the value of taking more of a “patient” approach oriented more towards building and operating effective local systems development systematically, rather than “result X by date Y”?

A: If I could answer this I’d probably get a Nobel Prize! So many organizations struggle with this and sadly there is no magic formula to address it. Politics change by election cycle so sustainability is also an issue.

In part, we need to question the advocacy messages and the ways of thinking that we instinctively bring to bear. It’s worth considering how much our approach to this is steered from our perspective as nutritionists, researchers, implementers and whether it might be better to approach it as if we were politicians. Using the tools of our own trade to address this problem we should be looking at suitable methodologies. For example, using Stakeholder Analysis to understand their thinking, dynamics, politics, influencers, accountabilities and motivators in order that we can design evidence, arguments and strategies that speak their language and be more likely to deliver effective results.

Q: A lot of studies that are meant to tackle some nutrition issues in Africa are conducted in Pilot, basically because of limited finances. Do you think setting up pilot studies are less effective and representative than setting up full-scale trials?

A: Both small scale pilots and larger national activities have their place and the relationship should be complementary. Clearly the population impact of a district based pilot will be smaller than a national effort, but if we are striving to improve implementation at scale, there is a need to test the water and go through a rigorous process of identifying bottlenecks and strategies to overcome them. By testing these at smaller scale, the mistakes are also smaller and the lessons learned can be applied at the larger scale to improve overall quality and impact. For example, you would have experience, examples and evidence to share with the ministries to influence and improve national programs.

Q: Do you think it’s worthwhile to develop specific implementation research frameworks for different nutrition interventions? For example, different frameworks for food fortification, micronutrient powders (MNPs) and supplementation.

A: Yes, there is definitely a case for developing different frameworks for different interventions and some are already out there, so we shouldn’t ‘reinvent the wheel’. There is a wealth of information that already exists, so we can leverage some quick wins from what is already out there and get some answers much faster than if we just engage in new empirical research. This requires us to have a much greater understanding of what does already exist, to uncover any inherent strengths and weakness and for us to go through a process of curation to assemble and share the most useful materials of the highest quality to the audiences that need them.

For example, the Home Fortification Technical Advisory Group (HF-TAG) has developed a very sophisticated manual and toolkit that lays out exactly what needs to be in place, what needs to be strong enough and what needs to be examined for effective MNP impact at scale. This provides the perfect framework for researchers to conduct the necessary assessments and inquiries at different parts of the system (across all of the Five Domains) to ultimately enhance any implementation activities.

It would be an enormous contribution to the field if an organization or group of organizations were to assemble exiting materials on nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions and ensure that the communities that need them know they are available and can access them. SISN might be able to convene this if it were supported to do so. If anyone is passionate about this and might be able to identify such sources of support please get in touch with us at info@implementnutrition.org.

Q: Would you elaborate on how IS approaches “gaps in knowledge utilization” rather than focusing on generating new knowledge? I understand not generating new knowledge, but how do we go about studying the “gaps” in the process of implementation?

A: Understanding the gaps is eminently researchable, albeit with tools that are less familiar to many in the nutrition community. It requires taking a systems view and conducting empirical research such as Stakeholder Analysis and Opinion Leader Research to determine: Where and how policy, planning and design and implementation decisions are being made? Who are the decision-makers (and shapers) and how are those interactions occurring? What knowledge (or frameworks or tools) are they currently using to make the decisions and what knowledge might they be missing; What are the decision-makers ‘default’ mental models of the implementation process? What are their priorities and the constraints they face (that may or may not be addressed by the decision shapers who are trying to influence outcomes)? Gaining this depth of understanding would provide valuable insight into the decision-making process in its entirety and illustrate how, (by whom, when and with what) it might be influenced in a more productive direction.

A recent Stakeholder Analysis in Ghana sought to do exactly this in relation to understanding how program managers and policy-makers make decisions about nutrition and what else influences national decision-making. You can read about the research here.

Q: You mention that implementation and implementation research are about planned efforts and understanding barriers in a process. Many of the areas in the Five Domains are areas that are often addressed in management schools. How much of what we need right now to address the ‘knowledge utilization gap’ can actually be filled by the IR agenda and/or by better ‘management’ of the implementation process, such as might be achieved by teaching management skills at university level?

A: In brief, a lot of it. So many of the weakness we have at organizational level and below are fundamentally management issues. If I were a nutrition manager in a country the first person I’d want to have on my team would be someone with up-to-date knowledge of management practices and innovations. One of the most common themes in the IS literature is that this emerging field is inter-, even trans-disciplinary. We as implementers sometimes struggle to get out of our comfort zones, but if we were willing to do so we might find that many of the challenges we face already have solutions from a host of other disciplines, including management science.

Q: How do we use existing evidence, for example the ‘evidence synthesis’ or ‘database’ initiatives that WHO has and how would this fit into the Framework?

A: SISN is currently working on an initiative to create a repository of curated information. As you can imagine a complex process which will involve deep analysis of any content such as what to adopt, how to adapt, what would be the implementation strategies and platforms, what capacities exist, when is it realistic to achieve, where and at what scale.

To influence implementation we need frameworks and tools that can facilitate that analysis and we need to ensure high awareness of any resources and ease of access to the information. In some cases, knowledge will need to be supported with technical assistance, knowledge brokering or coaching to help ensure planners and decision-makers at country level know what information is available to them and how best to apply it.

Q: What would be the best way to reach out to SISN if a project needs guidance, or would like to collaborate with the Society?

A: We currently have a number of ways for members to become more involved with the Society. We have a number of Working Groups convened on different topics and regularly post details on these when we are looking for volunteer support. These opportunities will steadily increase throughout 2018.

In terms of project support, we currently don’t have funding for this but are looking at a number or initiatives with other organizations such as SUN and IFPRI which might allow us to provide this in the future, potentially via a Global Consortium of experts and advisors.

Further information on the SISN Framework: webinar recording, pdf copy of the slides and a 5-page quick reference guide.

We welcome your thoughts, comments and questions on the above. Please send any feedback (including additional case study examples) to: info@implementnutrition.org.

To find out more about the benefits of SISN membership and to apply, please click here.

Further reading:

- Holt, D., et al., Toward a Comprehensive Definition of Readiness for Change: A Review of Research and Instrumentation. Research in Organizational Change and Development, 2006: p. 289 – 336.

- Weiner, B., A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implementation Science, 2009. 4(1): p. 67.

- Weiner, B., H. Amick, and S. Lee, Conceptualization and measurement of organizational readiness for change: a review of the literature in health services research and other fields. Med Care Res Rev, 2008. 65: p. 379 – 436.

- Stamatakis, K., et al., Measurement properties of a novel survey to assess stages of organizational readiness for evidence-based interventions in community chronic disease prevention settings. Implementation Science, 2012. 7(1): p. 65.

- Hall, K.L., et al., Moving the Science of Team Science Forward: Collaboration and Creativity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2008. 35(2, Supplement): p. S243-S249.